Can Utopian ideas help Architects to build better futures?

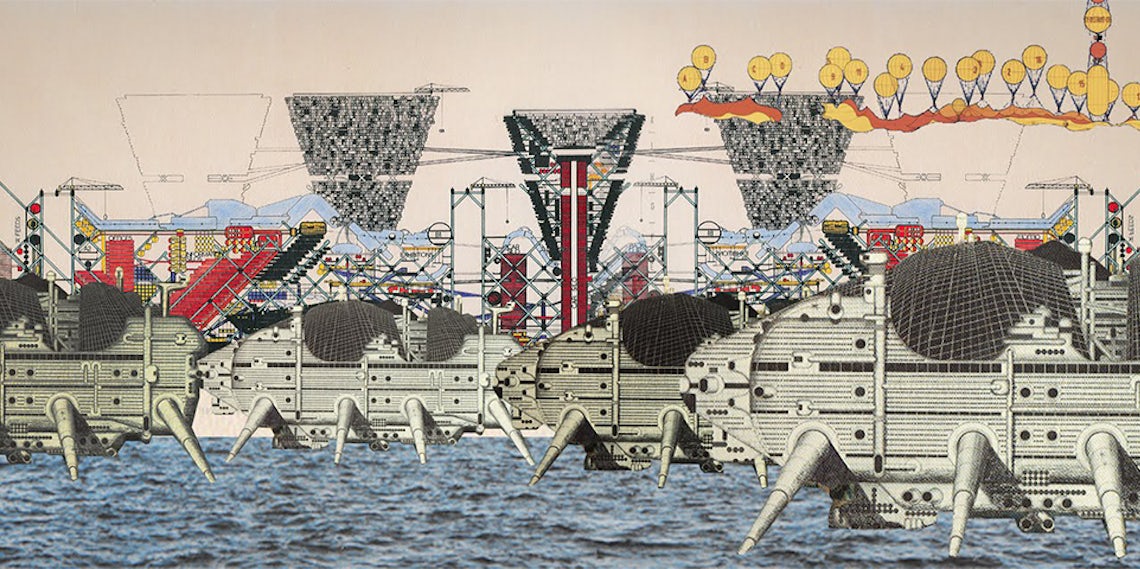

A style of Architecture- ‘fantastic’ or ‘visionary’, produced without the constraints of clients, budgets, materials, or planning regulations. “Utopia” derives from the Greek, meaning ‘no place’. Architecture and Utopia lead the reader beyond the architectural form in a broader perspective of relation. It leads to Architecture to society and the architect to the workforce and marketplace. And a few years ago, this particular subject of utopia and its relation to architecture was solely of historical interest. The utopian character of modern architecture has often been denounced and held it responsible for the mistakes of modern urbanism.

It is said that modern architects has jeopardized the quality of life in their attempts to change society. Italian historian Manfredo Tafuri, in his essay – Architecture and Utopia (1973) believed that the utopian streak of modern architecture was based on the fundamental delusion. And that Capitalism needed architectural and urban order to function in an efficient manner.

To counter this, Rem Koolhas and his followers tried to connect architecture with the real trends of the times, beginning with:

- Accelerated circulation of people

- Goods and money,

- Sprawling urbanization

The affinity of architecture and utopian thought is east to understand and when visionaries define the ideal life, they lay out a physical setting to establish and enhance its existence. Thus the relation between utopian intent and specific elements of architecture and design remains largely unexamined. The subsequent thinking of utopian thinking after the war was linked to parallels between utopian thinking and revolutionary ideologies.

Architecture is the will of an epoch translated into space – Mies Van Der Rohe. Hence, we are the first animal on the planet capable of imagining and realising new environments. We now live inbuilt space resulting from the realisation of another kind of utopia: the capitalist vision of individualism, consumerism, materialism and an insatiable appetite for the ‘new and different’.

Best Utopian Design Experiments around the world:

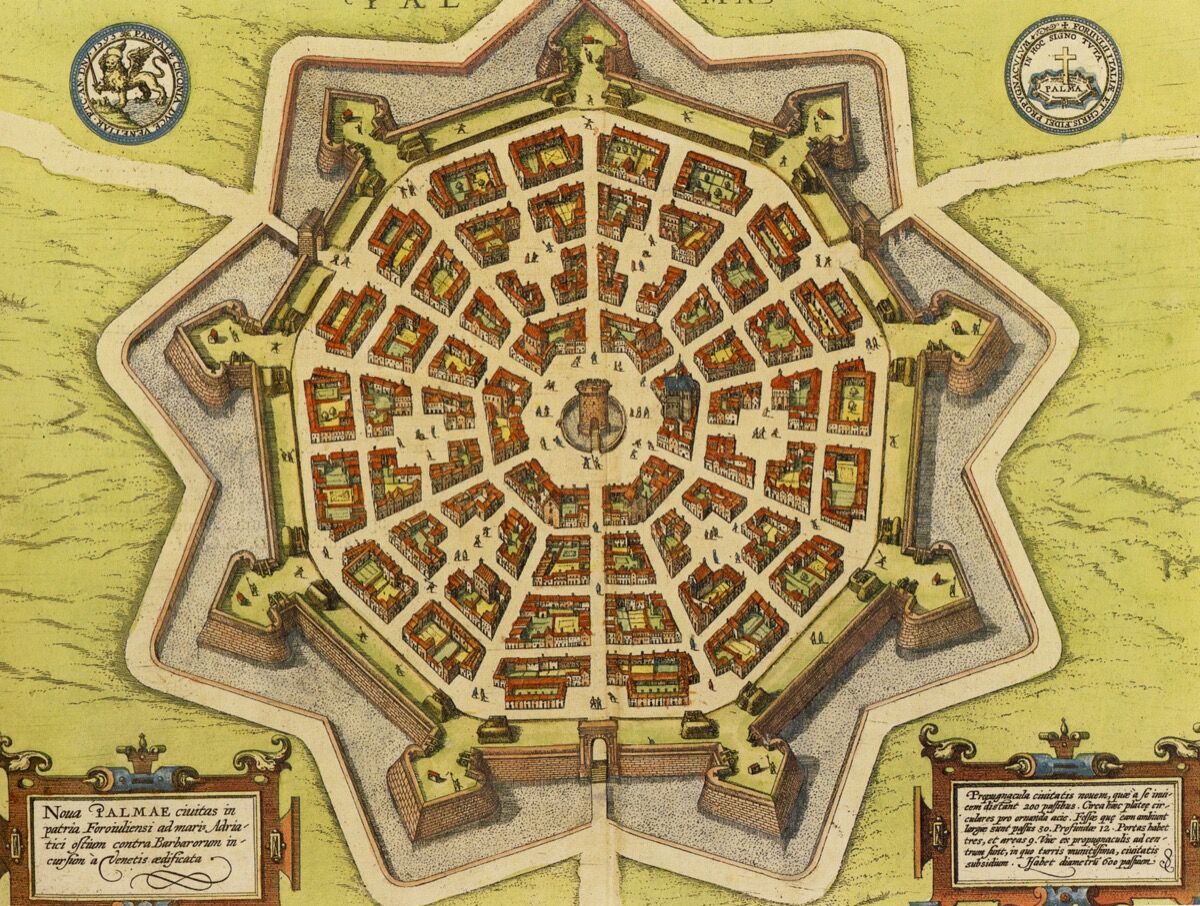

Palmanova, Italy

The Venetian model city of Palmanova was built strategically near what is now the Slovenian border to defend against the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century. It displayed the era’s cutting edge military features, including nine protruding ramparts as well as a surrounding moat and three guarded entryways. Its radial symmetry was intended to reflect the goodness of its incoming inhabitants, except no one wanted the risk of living in a military citadel. Perhaps, the Venetian government pardoned prisoners and gave them property in the city of fill it’s street. Palmanova is home to about 5,400 residents today.

Arcosanti, Arizona

Founded in 1970, the town is a brainchild of Italian architect Paolo Soleri, who envisioned a multi-story housing complex for 5,000 people. The people would grow their own food, bring no harm to the environment, and support themselves by producing and selling wind chimes. The town was expected to be completed within five years, but today is three per cent complete.

Drop City, Colorado

In 1965, three college graduates bought six acres of land in southern Colorado and it cost them $450. They established Drop City, a community in which punishment was prohibited, meals were communally prepared, and the property was shared among all. For a time period, the early inhabitants where ‘hippie commune’; they planted gardens, raised chickens, made art, and built their signature geodesic dome residences from recycled materials. As the number of residents and the use of illegal drugs escalated, members began abusing the communal funds for personal goods. Thus, it was difficult to stick to their no-punishment rule, and the founders eventually gave up and abandoned their utopian dream.

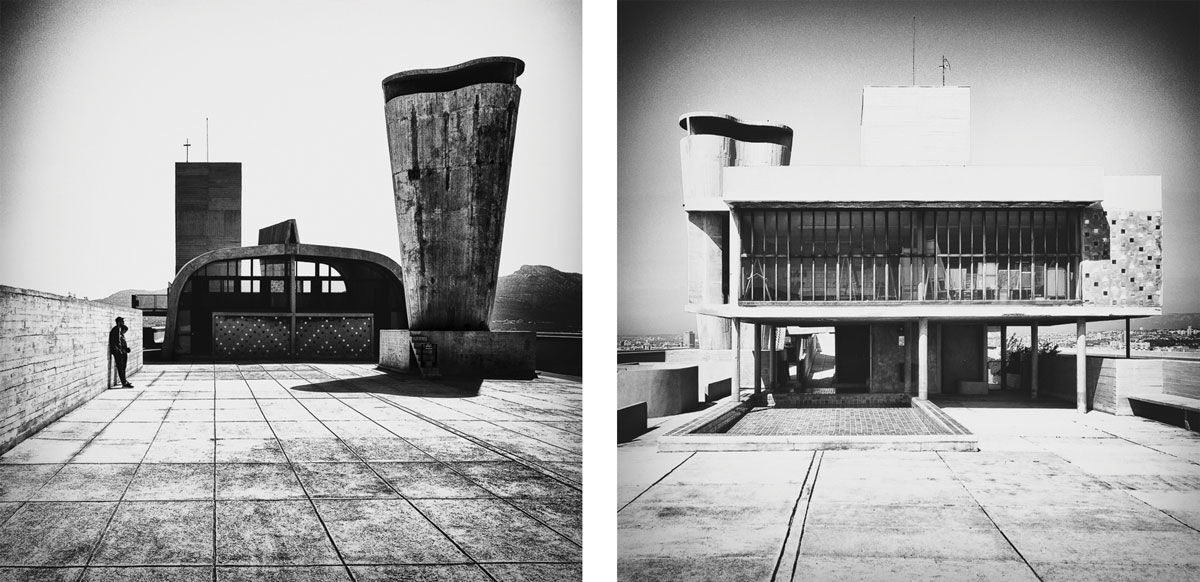

Le Corbusier’s Radiant City

Le Corbusier’s plan for the Ville Radieuse (Radiant City) was to operate as a ‘living machine’. Different areas would be designated for commercial, business, leisure, and residential purposes, a transportation deck in the city centre connecting city dwellers, via underground trains, to housing districts consisting of towering premade buildings called ‘UNITES”. Though it was envisioned as a utopian city, modern-day manifestations of Corbusier’s ideas have drawn criticism for their lack of public spaces and a general disregard for livability. Many of these principles went on to influence modern planning and urban housing complexes across the globe, but never actually came to fruition.

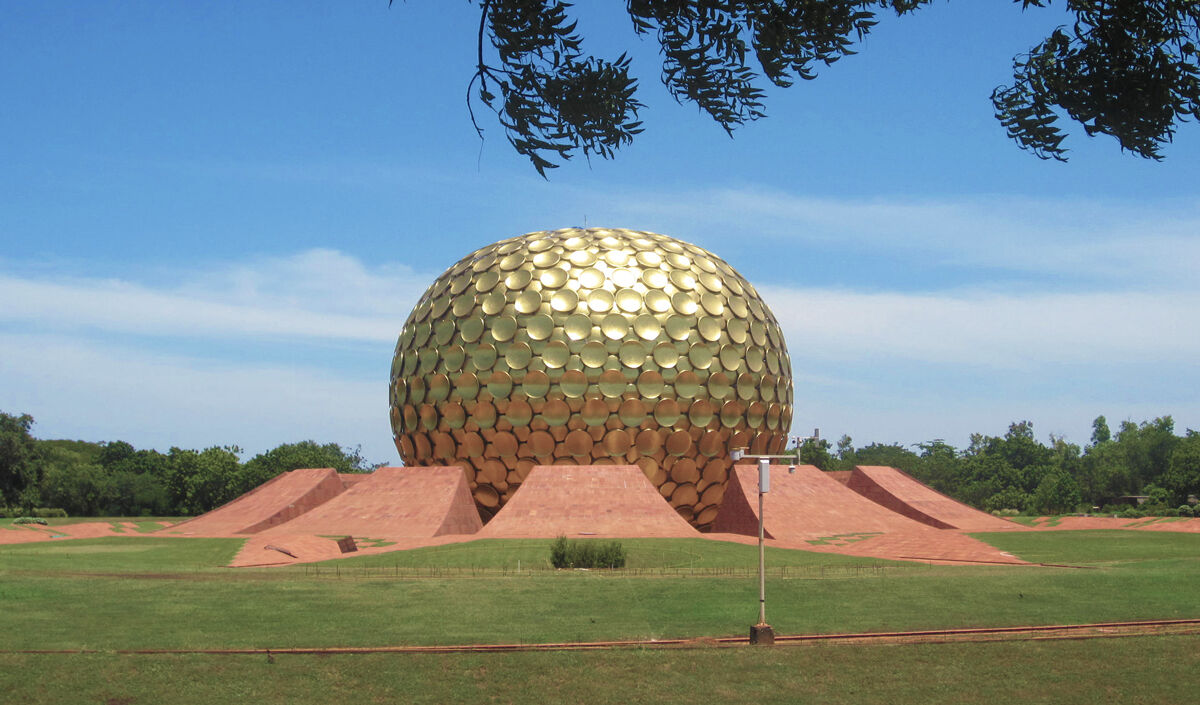

Auroville, India

Established in 1968, by Mirra Alfassa, a French woman also known as ‘the Mother’, Auroville (The city of Dawn) is the world’s largest spiritual utopia. A four-point charter outlines its founding ideals, including ‘belongs to humanity as a whole’ and that it will be a ‘place of an unending education, constant progress, and youth that never ages’. Duly protected by UNESCO and supported by the Indian government, Auroville is home to 2,500 people. Though its idealistic reputation has been undermined by questions of who controls its funds and whether its rules are actually followed.

Ordos, China

Numerous hastily constructed, nearly uninhabited ‘ghost towns’ have cropped up across China in the past decades as the country sees an unprecedented economic growth and real estate development. One of which is ‘Ordos 100’ – a larger than life architectural project with a huge statue of Genghis Khan overlooking central plaza. Featuring 100 villas designed by architects fro around the world. Yet this tremendous cost of building the city resulted in the highest property values, second to Shanghai. As rightly said by photographer, Raphael Olivier, ‘The whole place feels like a post-apocalyptic space station from a science fiction movie.’

Writer’s Viewpoint:

“The problem with utopia is the obsession with symmetry and perfection and its suppression of any individual impulse.” – Hugh Pearman

To achieve an idealised society is to ask people or force people into ways of living and behaving that has no denial, admits of no alternative. Architecturally, the same applies, as Architects are idealists and they want to make the world better with their skills and imagination. But there is always resistance, Utopias are dommes to crumble because of their political and physical, rigid and brittle take with resistant to further development.

Some Utopias were doomed, while some became the perfect solutions and ideal modules, as it has been a joint venture among the creator as well as the communities inhabitating. Though there is no wrong in dreaming and designing a better yet fairer society, but making an effort to implement it, is what matters.